Planetary boundaries

The planetary boundaries concept presents a set of nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come

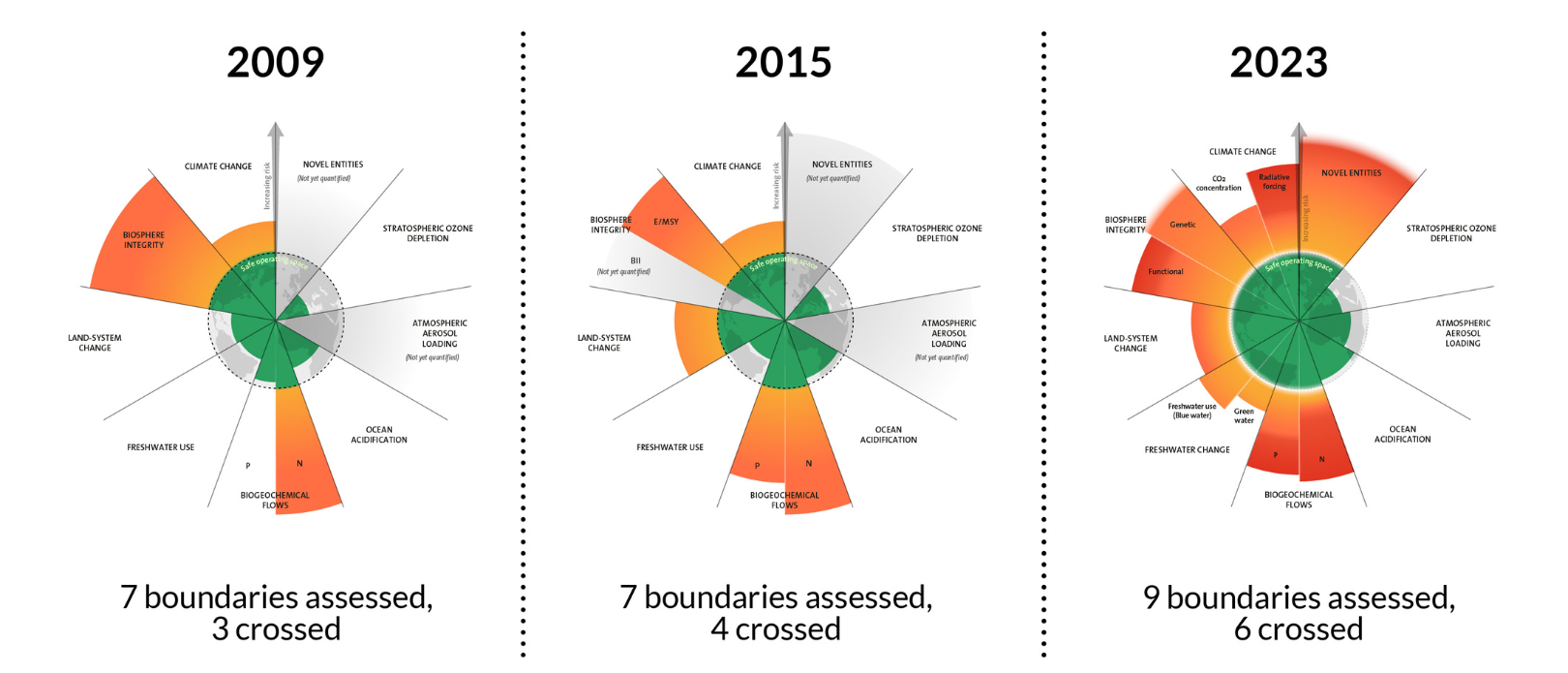

The evolution of the planetary boundaries framework. Licenced under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Credit: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. Based on Richardson et al. 2023, Steffen et al. 2015, and Rockström et al. 2009) Click on the image to download.

The planetary boundaries concept presents a set of nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come

In September 2023, a team of scientists quantified, for the first time, all nine processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system.

These nine planetary boundaries were first proposed by former centre director Johan Rockström and a group of 28 internationally renowned scientists in 2009.

Since then, their framework has been revised several times.

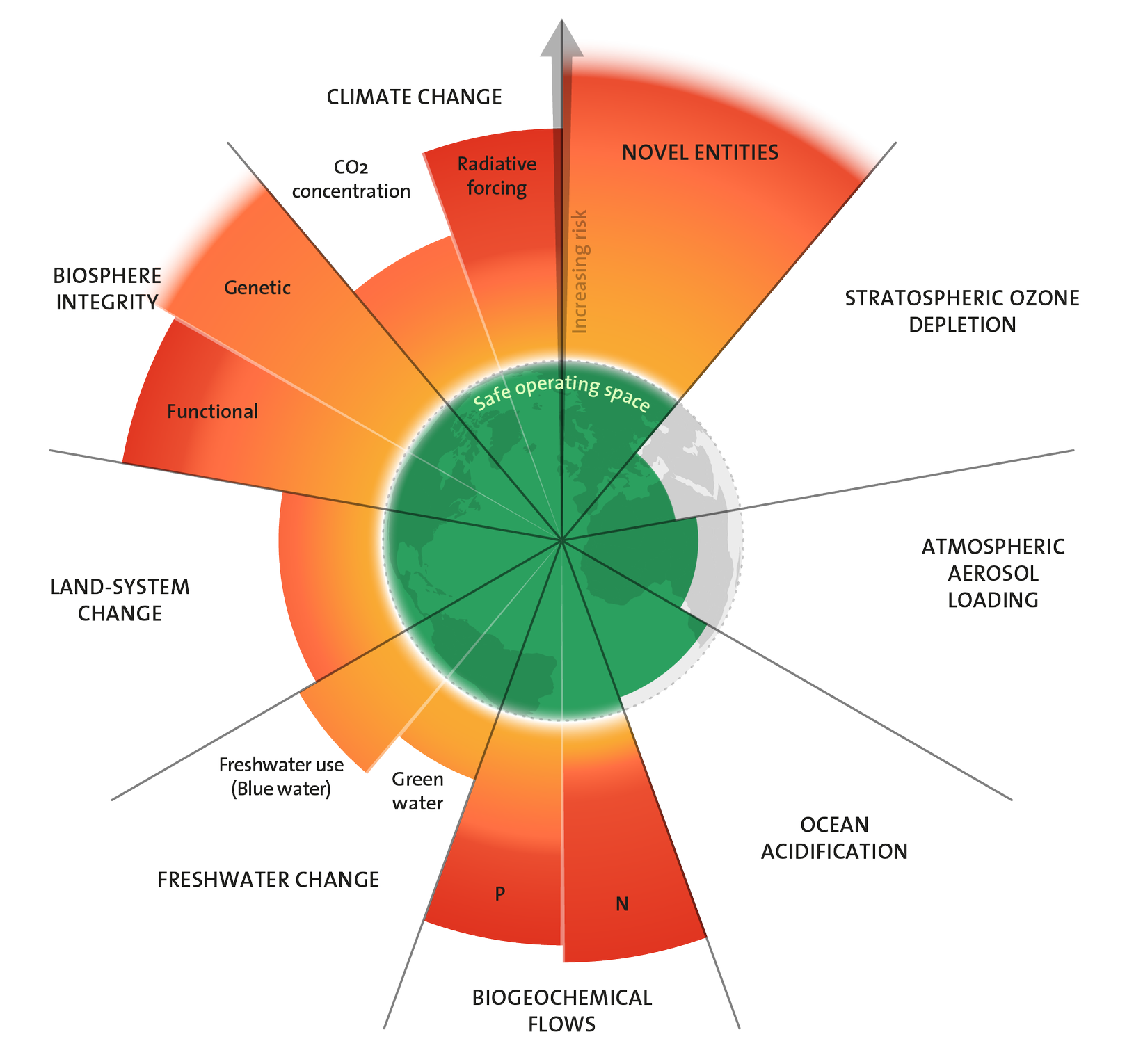

Now the latest update not only quantified all boundaries, it also concludes that six of the nine boundaries have been transgressed.

Crossing boundaries increases the risk of generating large-scale abrupt or irreversible environmental changes. Drastic changes will not necessarily happen overnight, but together the boundaries mark a critical threshold for increasing risks to people and the ecosystems we are part of.

Boundaries are interrelated processes within the complex biophysical Earth system. This means that a global focus on climate change alone is not sufficient for increased sustainability. Instead, understanding the interplay of boundaries, especially climate, and loss of biodiversity, is key in science and practice.

Since its first conceptualization, the planetary boundaries framework has generated enormous interest within science, policy, and practice.

The 2023 update to the Planetary boundaries. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Credit: “Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023”. Download the illustration here.

“A safe operating space for humanity

- Article: Published: 23 September 2009, Nature volume 461, pages472–475 (2009) Cite this article

“Identifying and quantifying planetary boundaries that must not be transgressed could help prevent human activities from causing unacceptable environmental change, argue Johan Rockström and colleagues.”

Authors:

- Johan Rockström,

- Will Steffen,

- Kevin Noone,

- Åsa Persson,

- F. Stuart Chapin III,

- Eric F. Lambin,

- Timothy M. Lenton,

- Marten Scheffer,

- Carl Folke,

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber,

- Björn Nykvist,

- Cynthia A. de Wit,

- Terry Hughes,

- Sander van der Leeuw,

- Henning Rodhe,

- Sverker Sörlin,

- Peter K. Snyder,

- Robert Costanza,

- Uno Svedin,

- Malin Falkenmark,

- Louise Karlberg,

- Robert W. Corell,

- Victoria J. Fabry,

- James Hansen,

- …

- Jonathan A. Foley

Summary

- New approach proposed for defining preconditions for human development

- Crossing certain biophysical thresholds could have disastrous consequences for humanity

- Three of nine interlinked planetary boundaries have already been overstepped

Although Earth has undergone many periods of significant environmental change, the planet’s environment has been unusually stable for the past 10,000 years1,2,3. This period of stability — known to geologists as the Holocene — has seen human civilizations arise, develop and thrive. Such stability may now be under threat. Since the Industrial Revolution, a new era has arisen, the Anthropocene4, in which human actions have become the main driver of global environmental change5. This could see human activities push the Earth system outside the stable environmental state of the Holocene, with consequences that are detrimental or even catastrophic for large parts of the world.

During the Holocene, environmental change occurred naturally and Earth’s regulatory capacity maintained the conditions that enabled human development. Regular temperatures, freshwater availability and biogeochemical flows all stayed within a relatively narrow range. Now, largely because of a rapidly growing reliance on fossil fuels and industrialized forms of agriculture, human activities have reached a level that could damage the systems that keep Earth in the desirable Holocene state. The result could be irreversible and, in some cases, abrupt environmental change, leading to a state less conducive to human development6. Without pressure from humans, the Holocene is expected to continue for at least several thousands of years7.

Planetary boundaries

To meet the challenge of maintaining the Holocene state, we propose a framework based on ‘planetary boundaries’. These boundaries define the safe operating space for humanity with respect to the Earth system and are associated with the planet’s biophysical subsystems or processes. Although Earth’s complex systems sometimes respond smoothly to changing pressures, it seems that this will prove to be the exception rather than the rule. Many subsystems of Earth react in a nonlinear, often abrupt, way, and are particularly sensitive around threshold levels of certain key variables. If these thresholds are crossed, then important subsystems, such as a monsoon system, could shift into a new state, often with deleterious or potentially even disastrous consequences for humans8,9.

Most of these thresholds can be defined by a critical value for one or more control variables, such as carbon dioxide concentration. Not all processes or subsystems on Earth have well-defined thresholds, although human actions that undermine the resilience of such processes or subsystems — for example, land and water degradation — can increase the risk that thresholds will also be crossed in other processes, such as the climate system.

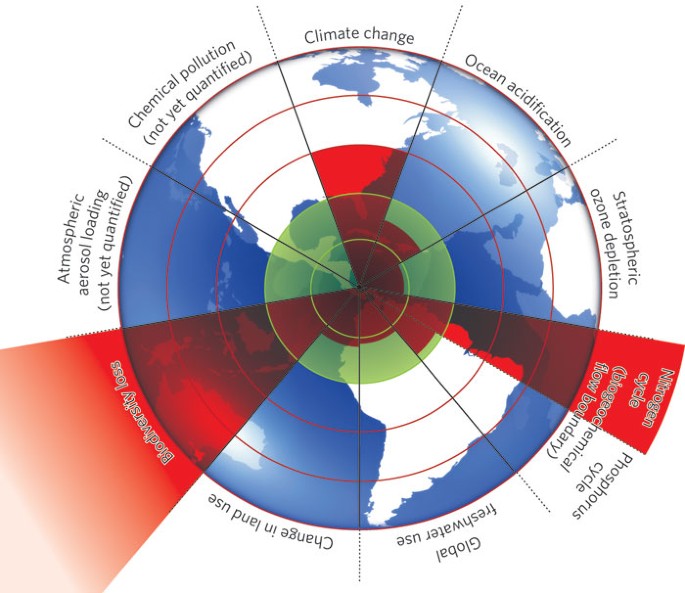

We have tried to identify the Earth-system processes and associated thresholds which, if crossed, could generate unacceptable environmental change. We have found nine such processes for which we believe it is necessary to define planetary boundaries: climate change; rate of biodiversity loss (terrestrial and marine); interference with the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles; stratospheric ozone depletion; ocean acidification; global freshwater use; change in land use; chemical pollution; and atmospheric aerosol loading (see Fig. 1 and Table).

Table 1 Planetary boundaries

In general, planetary boundaries are values for control variables that are either at a ‘safe’ distance from thresholds — for processes with evidence of threshold behaviour — or at dangerous levels — for processes without evidence of thresholds. Determining a safe distance involves normative judgements of how societies choose to deal with risk and uncertainty. We have taken a conservative, risk-averse approach to quantifying our planetary boundaries, taking into account the large uncertainties that surround the true position of many thresholds. (A detailed description of the boundaries — and the analyses behind them — is given in ref. 10.)

Humanity may soon be approaching the boundaries for global freshwater use, change in land use, ocean acidification and interference with the global phosphorous cycle (see Fig. 1). Our analysis suggests that three of the Earth-system processes — climate change, rate of biodiversity loss and interference with the nitrogen cycle — have already transgressed their boundaries. For the latter two of these, the control variables are the rate of species loss and the rate at which N2 is removed from the atmosphere and converted to reactive nitrogen for human use, respectively. These are rates of change that cannot continue without significantly eroding the resilience of major components of Earth-system functioning. Here we describe these three processes.

Climate change

Anthropogenic climate change is now beyond dispute, and in the run-up to the climate negotiations in Copenhagen this December, the international discussions on targets for climate mitigation have intensified. There is a growing convergence towards a ‘2 °C guardrail’ approach, that is, containing the rise in global mean temperature to no more than 2 °C above the pre-industrial level.

Our proposed climate boundary is based on two critical thresholds that separate qualitatively different climate-system states. It has two parameters: atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and radiative forcing (the rate of energy change per unit area of the globe as measured at the top of the atmosphere). We propose that human changes to atmospheric CO2 concentrations should not exceed 350 parts per million by volume, and that radiative forcing should not exceed 1 watt per square metre above pre-industrial levels. Transgressing these boundaries will increase the risk of irreversible climate change, such as the loss of major ice sheets, accelerated sea-level rise and abrupt shifts in forest and agricultural systems. Current CO2 concentration stands at 387 p.p.m.v. and the change in radiative forcing is 1.5 W m−2 (ref. 11).

There are at least three reasons for our proposed climate boundary. First, current climate models may significantly underestimate the severity of long-term climate change for a given concentration of greenhouse gases12. Most models11 suggest that a doubling in atmospheric CO2 concentration will lead to a global temperature rise of about 3 °C (with a probable uncertainty range of 2–4.5 °C) once the climate has regained equilibrium. But these models do not include long-term reinforcing feedback processes that further warm the climate, such as decreases in the surface area of ice cover or changes in the distribution of vegetation. If these slow feedbacks are included, doubling CO2 levels gives an eventual temperature increase of 6 °C (with a probable uncertainty range of 4–8 °C). This would threaten the ecological life-support systems that have developed in the late Quaternary environment, and would severely challenge the viability of contemporary human societies.

The second consideration is the stability of the large polar ice sheets. Palaeoclimate data from the past 100 million years show that CO2 concentrations were a major factor in the long-term cooling of the past 50 million years. Moreover, the planet was largely ice-free until CO2 concentrations fell below 450 p.p.m.v. (±100 p.p.m.v.), suggesting that there is a critical threshold between 350 and 550 p.p.m.v. (ref. 12). Our boundary of 350 p.p.m.v. aims to ensure the continued existence of the large polar ice sheets.

Third, we are beginning to see evidence that some of Earth’s subsystems are already moving outside their stable Holocene state. This includes the rapid retreat of the summer sea ice in the Arctic ocean13, the retreat of mountain glaciers around the world11, the loss of mass from the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets14 and the accelerating rates of sea-level rise during the past 10–15 years15.

Rate of biodiversity loss

Species extinction is a natural process, and would occur without human actions. However, biodiversity loss in the Anthropocene has accelerated massively. Species are becoming extinct at a rate that has not been seen since the last global mass-extinction event16.

The fossil record shows that the background extinction rate for marine life is 0.1–1 extinctions per million species per year; for mammals it is 0.2–0.5 extinctions per million species per year16. Today, the rate of extinction of species is estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times more than what could be considered natural. As with climate change, human activities are the main cause of the acceleration. Changes in land use exert the most significant effect. These changes include the conversion of natural ecosystems into agriculture or into urban areas; changes in frequency, duration or magnitude of wildfires and similar disturbances; and the introduction of new species into land and freshwater environments17. The speed of climate change will become a more important driver of change in biodiversity this century, leading to an accelerating rate of species loss18. Up to 30% of all mammal, bird and amphibian species will be threatened with extinction this century19.

Biodiversity loss occurs at the local to regional level, but it can have pervasive effects on how the Earth system functions, and it interacts with several other planetary boundaries. For example, loss of biodiversity can increase the vulnerability of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems to changes in climate and ocean acidity, thus reducing the safe boundary levels of these processes. There is growing understanding of the importance of functional biodiversity in preventing ecosystems from tipping into undesired states when they are disturbed20. This means that apparent redundancy is required to maintain an ecosystem’s resilience. Ecosystems that depend on a few or single species for critical functions are vulnerable to disturbances, such as disease, and at a greater risk of tipping into undesired states8,21.

From an Earth-system perspective, setting a boundary for biodiversity is difficult. Although it is now accepted that a rich mix of species underpins the resilience of ecosystems20,21, little is known quantitatively about how much and what kinds of biodiversity can be lost before this resilience is eroded22. This is particularly true at the scale of Earth as a whole, or for major subsystems such as the Borneo rainforests or the Amazon Basin. Ideally, a planetary boundary should capture the role of biodiversity in regulating the resilience of systems on Earth. Because science cannot yet provide such information at an aggregate level, we propose extinction rate as an alternative (but weaker) indicator. As a result, our suggested planetary boundary for biodiversity of ten times the background rates of extinction is only a very preliminary estimate. More research is required to pin down this boundary with greater certainty. However, we can say with some confidence that Earth cannot sustain the current rate of loss without significant erosion of ecosystem resilience.

Nitrogen and phosphorus cycles

Modern agriculture is a major cause of environmental pollution, including large-scale nitrogen- and phosphorus-induced environmental change23. At the planetary scale, the additional amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus activated by humans are now so large that they significantly perturb the global cycles of these two important elements24,25.

Human processes — primarily the manufacture of fertilizer for food production and the cultivation of leguminous crops — convert around 120 million tonnes of N2 from the atmosphere per year into reactive forms — which is more than the combined effects from all Earth’s terrestrial processes. Much of this new reactive nitrogen ends up in the environment, polluting waterways and the coastal zone, accumulating in land systems and adding a number of gases to the atmosphere. It slowly erodes the resilience of important Earth subsystems. Nitrous oxide, for example, is one of the most important non-CO2 greenhouse gases and thus directly increases radiative forcing.

Anthropogenic distortion of the nitrogen cycle and phosphorus flows has shifted the state of lake systems from clear to turbid water26. Marine ecosystems have been subject to similar shifts, for example, during periods of anoxia in the Baltic Sea caused by excessive nutrients27. These and other nutrient-generated impacts justify the formulation of a planetary boundary for nitrogen and phosphorus flows, which we propose should be kept together as one boundary given their close interactions with other Earth-system processes.

Setting a planetary boundary for human modification of the nitrogen cycle is not straightforward. We have defined the boundary by considering the human fixation of N2 from the atmosphere as a giant ‘valve’ that controls a massive flow of new reactive nitrogen into Earth. As a first guess, we suggest that this valve should contain the flow of new reactive nitrogen to 25% of its current value, or about 35 million tonnes of nitrogen per year. Given the implications of trying to reach this target, much more research and synthesis of information is required to determine a more informed boundary.

Unlike nitrogen, phosphorus is a fossil mineral that accumulates as a result of geological processes. It is mined from rock and its uses range from fertilizers to toothpaste. Some 20 million tonnes of phosphorus is mined every year and around 8.5 million–9.5 million tonnes of it finds its way into the oceans25,28. This is estimated to be approximately eight times the natural background rate of influx.

Records of Earth history show that large-scale ocean anoxic events occur when critical thresholds of phosphorus inflow to the oceans are crossed. This potentially explains past mass extinctions of marine life. Modelling suggests that a sustained increase of phosphorus flowing into the oceans exceeding 20% of the natural background weathering was enough to induce past ocean anoxic events29.

Our tentative modelling estimates suggest that if there is a greater than tenfold increase in phosphorus flowing into the oceans (compared with pre-industrial levels), then anoxic ocean events become more likely within 1,000 years. Despite the large uncertainties involved, the state of current science and the present observations of abrupt phosphorus-induced regional anoxic events indicate that no more than 11 million tonnes of phosphorus per year should be allowed to flow into the oceans — ten times the natural background rate. We estimate that this boundary level will allow humanity to safely steer away from the risk of ocean anoxic events for more than 1,000 years, acknowledging that current levels already exceed critical thresholds for many estuaries and freshwater systems.

Delicate balance

Although the planetary boundaries are described in terms of individual quantities and separate processes, the boundaries are tightly coupled. We do not have the luxury of concentrating our efforts on any one of them in isolation from the others. If one boundary is transgressed, then other boundaries are also under serious risk. For instance, significant land-use changes in the Amazon could influence water resources as far away as Tibet30. The climate-change boundary depends on staying on the safe side of the freshwater, land, aerosol, nitrogen–phosphorus, ocean and stratospheric boundaries. Transgressing the nitrogen–phosphorus boundary can erode the resilience of some marine ecosystems, potentially reducing their capacity to absorb CO2 and thus affecting the climate boundary.

The boundaries we propose represent a new approach to defining biophysical preconditions for human development. For the first time, we are trying to quantify the safe limits outside of which the Earth system cannot continue to function in a stable, Holocene-like state.

The approach rests on three branches of scientific enquiry. The first addresses the scale of human action in relation to the capacity of Earth to sustain it. This is a significant feature of the ecological economics research agenda31, drawing on knowledge of the essential role of the life-support properties of the environment for human wellbeing32,33 and the biophysical constraints for the growth of the economy34,35. The second is the work on understanding essential Earth processes6,36,37 including human actions23,38, brought together in the fields of global change research and sustainability science39. The third field of enquiry is research into resilience40,41,42 and its links to complex dynamics43,44 and self-regulation of living systems45,46, emphasizing thresholds and shifts between states8.

Although we present evidence that three boundaries have been overstepped, there remain many gaps in our knowledge. We have tentatively quantified seven boundaries, but some of the figures are merely our first best guesses. Furthermore, because many of the boundaries are linked, exceeding one will have implications for others in ways that we do not as yet completely understand. There is also significant uncertainty over how long it takes to cause dangerous environmental change or to trigger other feedbacks that drastically reduce the ability of the Earth system, or important subsystems, to return to safe levels.

The evidence so far suggests that, as long as the thresholds are not crossed, humanity has the freedom to pursue long-term social and economic development.

Editor’s note This Feature is an edited summary of a longer paper available at the Stockholm Resilience Centre (http://www.stockholmresilience.org/planetary-boundaries). To facilitate debate and discussion, we are simultaneously publishing a number of linked Commentaries from independent experts in some of the disciplines covered by the planetary boundaries concept. Please note that this Feature and the Commentaries are not peer-reviewed research. This Feature, the full paper and the expert Commentaries can all be accessed from http://tinyurl.com/planetboundaries.

References:

- Dansgaard, W. et al. Nature 364, 218–220 (1993).Article ADS Google Scholar

- Petit, J. R. et al. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Rioual, P. et al. Nature 413, 293–296 (2001).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Crutzen, P. J. Nature 415, 23 (2002).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Steffen, W., Crutzen, P. J. & McNeill, J. R. Ambio 36, 614–621 (2007).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Steffen, W. et al. Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure (Springer Verlag, 2004).Google Scholar

- Berger, A. & Loutre, M. F. Science 297, 1287–1288 (2002).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Scheffer, M., Carpenter, S. R., Foley, J. A., Folke C. & Walker, B. H. Nature 413, 591–596 (2001).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Lenton, T. M. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1786–1793 (2008).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Rockstrom, J. et al. Ecol. Soc. (in the press); available from http://www.stockholmresilience.org/download/18.1fe8f33123572b59ab800012568/pb_longversion_170909.pdf

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Solomon, S. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Hansen, J. et al. Open Atmos. Sci. J. 2, 217–231 (2008).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Johannessen, O. M. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett. 1, 51–56 (2008).Article Google Scholar

- Cazenave, A. Science 314, 1250–1252 (2006).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Church, J. A. & White, N. J. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, LO1602 (2006).Article ADS Google Scholar

- Mace, G. et al. Biodiversity in Ecosystems and Human Wellbeing: Current State and Trends (eds Hassan, H., Scholes, R. & Ash, N.) Ch. 4, 79–115 (Island Press, 2005).Google Scholar

- Sala, O. E. et al. Science 287, 1770–1776 (2000).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Sahney, S. & Benton, M. J. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 275, 759–765 (2008).Article Google Scholar

- Díaz, S. et al. Biodiversity regulation of ecosystem services in Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends (eds Hassan, H., Scholes, R. & Ash, N.) 297–329 (Island Press, 2005).Google Scholar

- Folke, C. et al. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 557–581 (2004).Article Google Scholar

- Chapin, F. S., III et al. Nature 405, 234–242 (2000).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Purvis, A. & Hector, A. Nature 405, 212–219 (2000).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Foley, J. A. et al. Science 309, 570–574 (2005).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Gruber, N. & Galloway, J. N. Nature 451, 293–296 (2008).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Machenzie F. T., Ver L. M. & Lerman, A. Chem. Geol. 190, 13–32 (2002).Article ADS Google Scholar

- Carpenter, S. R. Regime shifts in lake ecosystems: pattern and variation, Vol. 15 in Excellence in Ecology Series (Ecology Institute, 2003).Google Scholar

- Zillén, L., Conley, D. J., Andren, T., Andren, E. & Björck, S. Earth Sci. Rev. 91 (1), 77–92 (2008).Article ADS Google Scholar

- Bennett, E. M., Carpenter, S. R. & Caraco, N. E. BioScience 51, 227–234 (2001).Article Google Scholar

- Handoh, I. C. & Lenton, T. M. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1092 (2003).Article ADS Google Scholar

- Snyder, P. K., Foley, J. A., Hitchman, M. H. & Delire, C. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D21 (2004).Article Google Scholar

- Costanza, R. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2(2), 335–357 (1991).Article Google Scholar

- Odum, E. P. Ecology and Our Endangered Life-Support Systems (Sinuaer Associates, 1989).Google Scholar

- Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J. & Melillo, J. M. Science 277, 494–499 (1997).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Boulding, K. E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth in Environmental Quality Issues in a Growing Economy (ed. Daly, H. E.) (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966).Google Scholar

- Arrow, K. et al. Science 268, 520–521 (1995).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Bretherton, F. Earth System Sciences: A Closer View (Earth System Sciences Committee, NASA, 1988).Google Scholar

- Schellnhuber, H. J. Nature 402, C19–C22 (1999).Article CAS Google Scholar

- Turner, B.L. II et al. (eds) The Earth as Transformed by Human Action: Global and Regional Changes in the Biosphere over the Past 300 Years (Cambridge University Press, 1990).Google Scholar

- Clark, W. C. & Dickson, N. M. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8059–8061 (2003).Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

- Holling, C. S. The resilience of terrestrial ecosystems: local surprise and global change in Sustainable Development of the Biosphere (eds Clark, W. C. & Munn, R. E.) 292–317 (Cambridge University Press, 1986).Google Scholar

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R. & Kinzig, A. Ecol. Soc. 9, 5 (2004).Article Google Scholar

- Folke, C. Global Environmental Change 16, 253–267 (2006).Article Google Scholar

- Kaufmann, S. A. Origins of Order (Oxford University Press, 1993).Google Scholar

- Holland, J. Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity (Basic Books, 1996).Google Scholar

- Lovelock, J. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford University Press, 1979).Google Scholar

- Levin, S. A. Fragile Dominion: Complexity and the Commons (Perseus Books, 1999).Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kräftriket 2B, Stockholm, 10691, SwedenJohan Rockström, Will Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, Carl Folke, Björn Nykvist, Sverker Sörlin, Robert Costanza, Uno Svedin, Malin Falkenmark, Louise Karlberg & Brian Walker

- Stockholm Environment Institute, Kräftriket 2B, Stockholm, 10691, SwedenJohan Rockström, Åsa Persson, Björn Nykvist & Louise Karlberg

- ANU Climate Change Institute, Australian National University, Canberra ACT, 0200, AustraliaWill Steffen

- Department of Applied Environmental Science, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 10691, SwedenKevin Noone & Cynthia A. de Wit

- Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, 99775, Alaska, USAF. Stuart Chapin III

- Department of Geography, Université Catholique de Louvainé, 3 place Pasteur, Louvain-la-Neuve, B-1348, BelgiumEric F. Lambin

- School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, NorwichNorwich, NR4 7TJ, UKTimothy M. Lenton

- Aquatic Ecology and Water Quality Management Group, Wageningen University, PO Box 9101, HB Wageningen, 6700, the NetherlandsMarten Scheffer

- The Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, PO Box 50005, Stockholm, 10405, SwedenCarl Folke

- Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, PO Box 60 12 03, Potsdam, 14412, GermanyHans Joachim Schellnhuber

- Environmental Change Institute and Tyndall Centre, Oxford University, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UKHans Joachim Schellnhuber

- ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, 4811, Queensland, AustraliaTerry Hughes

- School of Human Evolution & Social Change, Arizona State University, PO Box 872402, Tempe, 85287-2402, Arizona, USASander van der Leeuw

- Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 10691, SwedenHenning Rodhe

- Division of History of Science and Technology, Royal Institute of Technology, Teknikringen 76, Stockholm, 10044, SwedenSverker Sörlin

- Department of Soil, Water, and Climate, University of Minnesota, 439 Borlaug Hall, 1991 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, 55108-6028, MN, USAPeter K. Snyder

- Gund Institute for Ecological Economics, University of Vermont, Burlington, 05405, VT, USARobert Costanza

- Stockholm International Water Institute, Drottninggatan 33, Stockholm, 11151, SwedenMalin Falkenmark

- The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment, 900 17th Street, NW, Suite 700, 20006, Washington DC, USARobert W. Corell

- Department of Biological Sciences, California State University San Marcos, 333 S Twin Oaks Valley Rd, San Marcos, 92096-0001, CA, USAVictoria J. Fabry

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2880 Broadway, New York, 10025, NY, USAJames Hansen

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organization, Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra, 2601, ACT, AustraliaBrian Walker

- Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UKDiana Liverman

- Institute of the Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, 85721, AZ, USADiana Liverman

- The Faculty for Natural Sciences, Tagensvej 16, Copenhagen N, 2200, DenmarkKatherine Richardson

- Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, PO Box 30 60, Mainz, 55020, GermanyPaul Crutzen

- Institute on the Environment, University of Minnesota, 325 VoTech Building, 1954 Buford Avenue, St Paul, 55108, MN, USAJonathan A. Foley

Additional information

See Editorial, page 447 . Join the debate. Visit http://tinyurl.com/boundariesblog to discuss this article. For more on the climate, see http://www.nature.com/climatecrunch .

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a